Lord Herbert Kitchener- Removal of Australian Memorials and Renaming Public Spaces Bearing his Name

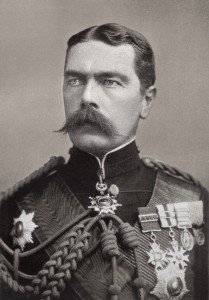

Herbert Horatio Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, is one of Britain’s most iconic military figures.

Playing a central role as Secretary of State for War in World War One, his face adorned one of the most famous wartime propaganda posters ever created, ‘Your Country Needs You’[i]

Prior to WW1 Kitchener, excelled as Britain’s military commander serving in Egypt as head of the Egyptian Army and Commander of Britain’s invasion of Sudan (1896-1899), winning notable victories at Atbara and Omdurman which awarded him fame as a dynamic military leader.

However, evidence shows another side of Kitchener, war crimes (summary execution of wounded combatants) committed on the battle field and atrocities against innocent civilians.

Kitchener and Australia

At the invitation of Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, Kitchener visited Australia in 1909 to inspect the existing state of defence preparedness of the Commonwealth, and advise on the best means of providing Australia with a land defence.

His tour of Australia included visits to review Army units in Queensland, NSWs, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. Memorials were erected and public spaces such as parks were named in his honor.[1]

This submission made to the Brisbane Council concerns Kitchener Park in Wynnum, Queensland and a granite Memorial stone to honour his review of troops from Lytton during his tour of Australia in 1910, advocates the renaming of the park and removal of the Memorial.

Similar submissions have been made to Mitchell Shire regarding a Memorial located at Seymour, Victoria commemorating his visit in 1910 and the naming of a hospital in Geelong, Victoria. (https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1579165)

As the world witnesses Vladimir Putin’s war crimes in Ukraine, his use of a scorched earth tactic and murder of innocent civilians, the comparison with Kitchener’s tactics in the Sudan and South Africa, his own war crimes, is a stark reminder that celebrating the military achievements of Commanders like Kitchener and Putin must be not attract Monuments to their barbarity.

Lord Kitchener

The evidence in support of this submission concerns Kitchener’s conduct that amounted to war crimes during military operations in the Sudan, (battle of the Omdurman), the Anglo Boer War and the illegal treatment in the trial and sentencing of three Australian volunteers, Lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton who served during the Boer war should give cause to review the appropriateness of this memorial.

Changing History?

Opponents to this proposal are reminded that history is not and should not be set in stone. The victors only get to write history, not dictate it and it is the duty of the generations that follow to decide whether they are deserving of their place in history – based on all the available evidence.

Kitchener’s journey through Australia was recognised and he is a part of our history. However, if evidence casts doubt on his reputation in warfare then a cogent argument exists to address his brutal transgressions as an inconvenient truth but a necessary journey.

Ben Boyd National Park

The decision in 2022 to re-name the Ben Boyd National Park in New South Wales set a precedent relevant to the Kitchener matter.[ii]

‘The park was established in 1971 covering 8,900 hectares (35 sq. mi.) and was originally named after Benjamin Boyd. In September 2022 after consultations with more than 60 representatives from Aboriginal and South Sea Islander communities the park was renamed Beowa. Boyd was a wealthy pastoralist and businessman in the 1840s, with interests in shipping (including whaling),[4][5] based on the South Coast of NSW. At the time, the area was part of the District of Port Phillip and Boyd was elected to the NSW Legislative Council for the electoral district of Port Phillip. He was the first in Australia to engage in blackbirding, a practice akin to slavery, when a ship he had commissioned brought 65 Melanesian labourers to Boyd Town in 1847′.

The decision to rename Boyd Park to Beowa Park did not denigrate Ben Boyd’s role as a landholder, grazier, entrepreneur, banker and business man in NSW’s and politician in the Legislative Council. However, the evidence of his involvement in slavery for commercial gain was significant in recognition of Boyd’s practice of ‘blackbirding’, the taking people from Pacific islands to work on his pastoral stations was recognised as illegal and inhumane.

The fundamental proposition to rename a public site in the light of evidence of oppressive/illegal conduct is relevant to the Kitchener proposal as it is to the Boyd matter.

Background

While memorials to Kitchener in Australia or elsewhere, including England, celebrate his contribution to British military, they fail to take into account the brutal and illegal manner by which he achieved victory in Sudan and South Africa. Even by the standards of the day, his prosecution of these military campaigns was a ruthless departure from all humanitarian conventions governing warfare and left himself exposed to accusations of war crimes.

Australian Councils and Government agencies that recognise Kitchener must reconsider. Kitchener’s military exploits in the prosecution of the war against the Boer Republics and in the Sudan are noted, but they fail to recognise his brutal treatment of combatants and non combatants in these military operations.

While Kitchener is recognised on Memorials and public spaces was appropriate in 1910, 112 years later it fails to recognise the illegal conduct that Kitchener used in the campaigns he commanded. The charges against him include; the murder of wounded combatants, the persecution of non combatants and the destruction of their homes, property including live stock and farming produce through the use of a scorched earth policy and causing their death through the use of concentration camps used to intern civilians. These charges are not speculation, but a matter of historical record. While the victor gets to write history, it does not follow that generations that follow should be required to honour those misdeeds. We should no more celebrate the deeds of Lord Kitchener as we should those of Vladimir Putin in the Ukraine, with which there is a chilling parallel.

Sudan-1882 -Kitchener’s Conduct

‘The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of the Mahdist Islamic State, led by Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. The battle took place on 2 September 1898, at Kerreri, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) north of Omdurman in the Sudan’.[iii]

12,000 Muslim warriors were killed, 13,000 wounded and 5,000 taken prisoner.

Kitchener’s brutal and summary execution of the wounded enemy on the battlefield was condemned:

‘Controversy over the killing of the wounded after the battle began soon afterwards.[14] The debate was ignited by a highly critical article published by Ernest Bennett (present at the battle as a journalist) in the Contemporary Review, which evoked a fierce riposte and defence of Kitchener by Bennet Burleigh (another journalist also present at the battle).[15][16] Winston Churchill privately agreed with Bennett that Kitchener was too brutal in his killing of the wounded.[17] This opinion was reflected in his own account of the battle when it was first published in 1899.[18’

Kitchener’s decisive victory in the Sudan and celebrated by the British Government was over shadowed by his conduct by none other than Winston Churchill who served as a soldier and reporter at the battle. Churchill was an eye witness to the brutality of Kitchener’s campaign to eliminate the Mahdist Islamic State in the Sudan.

Michelle Gordon’s compelling study into Kitchener’s conduct during the war focused on colonial violence by the British Empire, mass violence, genocide that exceeded legitimate rules of engagement and focused on the massacre and looting of wounded enemy soldiers even though some 5000 enemy were taken prisoner.[iv]

Gordon argued under Kitchener’s command, a policy of revenge to acquit the brutal death of General Charles Gordon and his British troops by Mahdist troops. Gordon had travelled to Khartoum to oversee the withdrawal of the Egyptian military and the civilian population in response to the rise of an Islamic movement.

While Kitchener’s war was justified, to enforce British control over Egypt, Gordon’s research including photographic evidence of the brutality; ‘This battle entailed a range of appalling acts on the part of the Anglo-Egyptian army, including the massacring of the enemy wounded’.[v]

Anglo Boer War 1899-1902

Kitchener’s conduct:

‘During the last 18 months of the war, Kitchener combated guerrilla resistance by such methods as burning Boer farms and herding Boer women and children into disease-ridden concentration camps. These ruthless measures, and Kitchener’s strategic construction of a network of blockhouses across the country to localize and isolate the Boers’ forces, steadily weakened their resistance’.[vi]

From December 1899, the British brought in large numbers of troops and mounted a successful counter-offensive. Eventually more than 500,000 soldiers fought for the British against only 50,000 Boers. The vast numerical difference led the Boers to employ irregular, guerrilla tactics and eventually the British followed suit. During the guerrilla phase of the war, the British Army, commanded by Lord Kitchener, sought to cut the Boer commandos off from their food supplies and the support of their families.

This meant destroying Boer farms and interning civilians in concentration camps. There, weakened by malnutrition, 28,000 Boer women and children and at least 20,000 Africans died of disease. The strategy was brutally effective and the Boers surrendered in May 1902. As part of the British Empire, the Australian colonies (and after 1900, the Australian federal government) provided volunteer troops for the war. As many as 16,000 Australians fought in the Boer War. Almost 600 died.

Australians at home initially supported the war but became disenchanted as the conflict dragged on, especially as the suffering of the Boer civilians became known.[vii] Several years previously, from 1900 to 1902, Kitchener was commander of the British army in South Africa in the Second Boer War.

He ordered that all Boer farms should be destroyed under his “scorched earth” policy .This included the systematic destruction of the Boers’ crops and the slaughtering of all livestock, the burning down of homesteads, the poisoning of wells and the salting of fields.

This was in order to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. This policy included the incarceration of tens of thousands of women and children, who were forcibly moved into 45 concentration camps throughout the Transvaal. There were another 64 concentration camps for black Africans who had made the serious error of supporting the Boers.

More than 26,000 Afrikaans women and children died in these camps. We do not have any figure for the similar number of black Africans who died, as the British army did not regard them as important enough to keep records. To those in London who are organising this year of commemoration of the First World War, Horatio Kitchener is a war hero. To my mind he is a war criminal.[viii]

‘Following the defeat of the conventional Boer forces, Kitchener succeeded Roberts as overall commander in November 1900.[52] He was also promoted to lieutenant-general on 29 November 1900[3][53] and to local general on 12 December 1900.[52] He subsequently inherited and expanded the successful strategies devised by Roberts to force the Boer commandos to submit, including concentration camps and the burning of farms.[18] Conditions in the concentration camps, which had been conceived by Roberts as a form of control of the families whose farms he had destroyed, began to degenerate rapidly as the large influx of Boers outstripped the ability of the minuscule British force to cope. The camps lacked space, food, sanitation, medicine, and medical care, leading to rampant disease and a very high death rate for those Boers who entered. Eventually 26,370 women and children (81% were children) died in the concentration camps.[54] The biggest critic of the camps was the English humanitarian and welfare worker Emily Hobhouse.[55] She published a prominent report that highlighted atrocities committed by Kitchener’s soldiers and administration, creating considerable debate in London about the war.[56] Kitchener blocked Hobhouse from returning to South Africa by invoking martial law provisions.[56]

Historian Caroline Elkins characterized Kitchener’s conduct of the war as a “scorched earth policy”, as his forces razed homesteads, poisoned wells and implemented concentration camps, as well as turned women and children into targets in the war.[ix]

The death rate for Boer civilians in the concentration camps in South Africa exceeded this by a factor of 10. It’s well established that 28 000 white people and 20 000 black people died in various camps in South Africa. Between July 1901 and February 1902 the rate was, on average, 247 per 1000 per annum in the white camps. It reached a high of 344 per 1000 per annum in October 1901 and a low of 69 per 1000 per annum in February 1902’.

Kitchener’s -Concentration Camps and Scorched Earth strategy Contrary to the Hague Convention of 1899

Emily Hobhouse, an English philanthropist, a social worker was a powerful critic of Kitchener. Hobhouse was appointed secretary of the South African Conciliation Committee, which was a group that opposed the British government policy regarding South Africa. Hobhouse was a humanitarian and pacifist who came to visit South Africa in December 1900, during the Anglo Boer War.

‘Hobhouse visited concentration camps set up by the British in the OFS and Transvaal. When Hobhouse arrived at the camps, she was appalled to see the conditions in which the women and children were forced to live in. For several months Hobhouse attempted to improve the living conditions of the Boers and in many cases provided them with some supplies and clothing. Eventually, Hobhouse also attempted to voice her concerns to the British administration at these camps and Lord Kitchener himself. However, Hobhouse was unsuccessful in her attempts to persuade the administration to make efficient changes and therefore, decided to travel back to England where she voiced her opposition to the concentration camps and reported on the appalling conditions in these camps. She focused her campaign on the liberal opposition, and in this way was instrumental in the government decision to send a group of women, under Dame Millicent Fawcett, to look at the situation.’[x]

Her advocacy was resisted by the British Government as it sought to protect Kitchener’s reputation but also the Government’s endorsement of his aggressive policies to subjugate the Boers into submission through extreme measures that were contrary to the then existing rules of war.

‘The British commander, Lord Kitchener, devised a scorched-earth policy against the commandos and the rural population supporting them, in which he destroyed arms, blockaded the countryside, and placed the civilian population in concentration camps. Some 25,000 Afrikaner women and children died of disease and malnutrition in these camps, while 14,000 Blacks died in separate camps. In Britain the Liberal opposition vehemently objected to the government’s methods for winning the war.[xi]

‘Those that would argue that the destruction that was wrought during the period when General Lord Kitchener exercised his well-known “Scorched Earth Policy”, whereby all Boer farms were destroyed, and the inhabitants taken to concentration death camps was justifiable are generally in the minority.

It was in these camps that between 25,000 and 29,000 Boer women and children died, not to mention the more than 15,000 thousand black people whose deaths and numbers were never properly recorded. This method of warfare has left seeds of bitterness which today, after one hundred years, has still not entirely been forgotten.

The scorched earth policy led to the destruction of about 3000 Boer farmhouses and the partial and complete destruction of more than forty towns. Thousands of women and children were removed from their homes by force. They had little or no time to remove valuables before the house was burnt down. They were taken by ox wagons or in open cattle trucks to the nearest camp.

A Boer family looks on at their house that was set alight by the British forces during the South African War. Photographical Collection Anglo-Boer War Museum, Bloemfontein SA[xii]

The death rate for Boer civilians in the concentration camps in South Africa exceeded this by a factor of 10. It’s well established that 28 000 white people and 20 000 black people died in various camps in South Africa. Between July 1901 and February 1902 the rate was, on average, 247 per 1000 per annum in the white camps. It reached a high of 344 per 1000 per annum in October 1901 and a low of 69 per 1000 per annum in February 1902.

These families were taken against their will. They were forcibly put on ox wagons and open railway trucks and taken to the camps. They were not, as Rees-Mogg claimed, moved for their protection and safety. Nor were they moved to the camps to be fed. Rather, their internment had everything to do with ending the resistance of Boers still fighting the British.

Lizzie van Zyl, a Boer child, visited by Emily Hobhouse in a British concentration camp

These camps were built by British soldiers amid the Boer War, during which the British rounded up Dutch Boers and native South Africans and locked them into cramped camps where they died off by the thousands.

This is where the word “concentration camp” was first used – in British camps that systematically imprisoned more than 115,000 people and saw at least 25,000 of them killed off. In fact, more men, women, and children died of starvation and disease in these camps than did men actually fighting in the Second Boer War of 1899 to 1902, a territorial struggle in South Africa.

As the Boer War raged on, however, the British became more brutal. They introduced a “scorched earth” policy. Ever Boer farm was burned to the ground, every field salted, and every well poisoned. The men were shipped out of the country to keep them from fighting, but their wives and their children were forced into the camps, which were quickly become overcrowded and understocked.

Soon, there were more than 100 concentration camps across South Africa, imprisoning more than 100,000 people. The nurses there didn’t have the resources to deal with the numbers. They could barely feed them. The camps were filthy and overrun with disease, and the people inside started to die off in droves. The children suffered the most. Of the 28,000 Boers that died, 22,000 were children. They were left to starve, especially if their fathers were still fighting the British in the Boer War. With so few rations to pass around, the children of fighters were deliberately starved and left to die.[xiii]

A crowd of Boer children, photographed inside of a concentration camp. One in four would not make it out alive.

Nylstroom Camp, South Africa. 1901. Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science

Hague Conventions of 1899 – Non Combatants

The Hague Convention of 1899 was the treaty on the rights of non combatants. England was a signatory to the Treaty.[xiv] Military operations under the command of Kitchener established the following articles were breached.

While the Convention recognized entrenched war as a legitimate mode of settling disputes between the States. The Hague undertakings were driven by the “desire to diminish the evils of war so far as military necessities permit”.

The Hague undertakings agreed to by the signatory States were driven by the “desire to diminish the evils of war so far as military necessities permit” [xv]

Civilians under Convention were persons who are not members of the armed forces and are not combatants were protected under the treaty.

Article 25 of Treaty II stated that undefended communities are protected from any form of attack. ‘The attack or bombardment of towns, villages, habitations or buildings which are not defended, is prohibited’.

Article 28 also provided: ‘the pillage of a town or place, even when taken by assault, is prohibited’.

Article 46 provided: ‘Family honors and rights, individual lives and private property, as well as religious convictions and liberty, must be respected’. Private property cannot be confiscated’.

Article 47 ‘Pillage is formally prohibited’.

House of Commons – Owen Humphreys, MP & John Dillon, MP

On 04 March 1902, Owen Humphreys, MP raised his concerns with Government about the prosecution of the war through the use of a scorched earth policy and the operation of concentration camps. His allegations were directed at Military Commander, including Lord Kitchener.

He argued:[xvi]

- The camps were structured as a military strategy: ‘There can be little doubt that in the first instance the military did not take sufficiently into account the difference necessary between the treatment of women and children and that of soldiers’.

- The camps were over populated, medical facilities were primitive and disease, malnutrition and poor sanitary was appalling; ‘the camp a prey to a terrible outbreak of disease—measles, enteric, pneumonia, malaria, chicken-pox, and whooping-cough, which was undoubtedly fostered and aggravated by the insanitary conditions’.

- ‘The condition of women and children captured on commando and sent into camp is pitiable in the extreme. They arrive here with nothing, and report destruction of even their mattresses and blanket’s.

- ‘One of the chief causes of the great mortality is stated by the medical men to have been that a large number of children had no bedsteads whatever, and were obliged to sleep on beds on the ground, with the result that they were frequently wet and miserable. Another fault of military policy was the wretched system of half rations’.

- Civilians in the camps were treated as prisoners and were not free to leave the camps;

- ‘Lord Kitchener did not provide reasonable provision for the wants of shelter and food for the unhappy people turned out of these farms’.

- Under Lord Kitchener’s direction, concentration camps an essential part of his military scheme of operations against those still fighting.

- Mr Humphrey’s concluded; ‘When historians in the future come to consider the policy which underlay the formation of these camps, they will regard it as one of the saddest chapters of English history’.

- He successfully moved a motion critical of the Government regarding the deplorable mortality in the concentration camps formed in the execution of the policy of clearing the country in South Africa;

‘Bringing the figures down to the end of January, I find that 14,284 children and 2,484 men and women have perished in them. This is a terrible loss, but it is still more terrible when you consider the proportion which this mortality bears to the numbers in the camps themselves. Repeatedly the death rate of children has been something like 500 per 1,000 per annum, and even now, in the returns for January last, I find the death rate is 247 per 1,000. Now, when such a tragedy as this is unrolled before our eyes it is necessary—indeed, it is more—it is the duty of Parliament to inquire strictly into what are the causes and what are the remedies which should be provided’.

Mr Dillon addressed the House of Commons and made a number of allegations against the British military concerning barbaric and illegal practices used to prosecute the war and Kitchener’s illegal conduct in prosecuting the Boer war.[xvii]

His address includes evidence that methods used included orders to take no prisoners, destroy Boer farms, (thus denying guerrillas of necessary logistical support) and to imprison Boer civilians and their families in concentration camps where cruel treatment was applied to force surrender of Boer fighters. The following extracts are compelling:[xviii]

‘But I pass over these details to the fact, which was only obtained by the process of squeezing Ministers, the shameful fact admitted by the Secretary of State for War to-day, that in the prison camps and so-called refugee camps of the Orange Free State the women and children of those who are out on commando, and who declined to surrender, are put on half rations and informed that they will be kept on that allowance until their husbands or brothers come in and surrender. Is there any parallel for the cruelty and meanness of that in the whole history of war? For my part I never read of any proceedings so mean and cruel and so cowardly—to endeavour to overcome these men—whom you cannot, although you are ten to one, beat in the field—to seek to force and intimidate them into surrender by starving their women and children?[xix]

In Dillon’s address he referred to evidence probative of tactics used by the British military to defeat guerrilla combatants.

When hon. Members call into question the burning of farms, what is the reply? It is said that if it be good policy to end the war, then whatever tends to bring the war to a speedy conclusion is good policy.[xx]

the shameful fact admitted by the Secretary of State for War to-day, that in the prison camps and so-called refugee camps of the Orange Free State the women and children of those who are out on commando, and who declined to surrender, are put on half rations and informed that they will be kept on that allowance until their husbands or brothers come in and surrender. Is there any parallel for the cruelty and meanness of that in the whole history of war? For my part I never read of any proceedings so mean and cruel and so cowardly—to endeavour to overcome these men—whom you cannot, although you are ten to one, beat in the field—to seek to force and intimidate them into surrender by starving their women and children.

in the course of what took place here last night, that a policy of devastation, of carrying fire and sword through these countries, was justifiable, not on the ground that you are dealing with treachery, but to make those countries uninhabitable to the enemy. I denounce that as an outrage on the usages of war as recognised to-day by every civilised country throughout the world. and it is admitted that this policy of starving women and children is adopted

Dillon’s Statement – Criticism of Kitchener’s conduct contrary to law

At the conclusion of the debate regarding the treatment of civilians during the Boer war, Dillon argued were contrary to the usages of war, the House passed the following motion: [xxi]

‘But we humbly represent to Your Majesty that the wholesale burning of farmhouses, the wanton destruction and looting of private property, the driving of women and children out of their homes without shelter or proper provision of food, and the confinement of women and children in prison camps are practices not in accordance with the usages of war as recognised by civilised nations; that such proceedings are in the highest degree disgraceful and dishonouring to a nation professing to be Christian, and are calculated by the intense indignation and hatred of the British name which they must excite in the Dutch population to immensely increase the difficulty of restoring peace to South Africa. And we humbly and earnestly present to Your Majesty that it is the duty of Your Majesty’s Government immediately to put a stop to all practices contrary to the recognised usages of war in the conduct of the war in South Africa; and to make an effort to bring the war to an end by proposing to the Governments of the two Republics such terms of peace as brave and honourable men might, under all the circumstances, be reasonably expected to entertain.’

Kitchener’s Illegal Orders –Evidence of Summary Execution

Mr. Dillon also made claims about illegal orders not to take prisoners issued by Kitchener. The following quotes are significant as they refer to verbatim quotes from three letters written by British soldiers.[xxii]

‘I turn now from this subject—this painful and humiliating subject—to another aspect of the war, I say there is sufficient evidence to demand from you an immediate, serious and searching investigation. What is this charge? It is that Lord Kitchener has recently in the Transvaal repeated what he is alleged to have done on the eve of Omdurman— namely, that he conveyed to his officers secret instructions to take no prisoner. That charge was first published in a letter in the Freeman’s Journal, Dublin. The real charge made is that private instructions were issued to take no prisoners.

The orders in this district from Lord Kitchener are to burn and destroy all provisions, forage, etc., and seize cattle, horses, and stock of all sorts, wherever found, and to leave no food in the houses for the inhabitants. This applies to houses occupied by women and children only. And the word has been passed round privately that no prisoners are to be taken; that is, all the men found fighting are to be shot. This order was given to me personally by a general, one of the highest in rank in South Africa. So there is no mistake about it. The instructions given to the columns closing round De Wet north of the Orange River are that all men are to be shot, so that no tales may be told; also the troops are told to loot freely from every house, whether the men belonging to the house are fighting or not.[xxiii]

A letter signed by William Clyne, of the Liverpool Regiment, which was published in the Liverpool Courier. It contains this statement— Lord Kitchener has issued orders that no man has to bring in any Boer prisoners; if he does he has to give him half his rations for the prisoner’s keep. Lord Roberts was too lenient with the Boers. De Wet sent in to General Knox asking for an armistice. Lord Kitchener told General Knox to keep on shelling him while he brought up reinforcements. That was the armistice he got. I turn to a letter from Private John Harris, of the Royal Welsh Regiment, published in the Wolverhampton Express and Star, which states— We take no prisoners now. … There happened to be a few wounded Boers left. We put them through the mill. Every one was killed. I give these letters for what they are worth. I wish to be perfectly frank in this matter, and not to put my evidence stronger than it is’.[xxiv]

Dillon’s charge against Kitchener was that he conveyed to his officers secret instructions to take no prisoners. Dillon quoted evidence from a number of sources including letters written by Private Harris and others. Dillon quoted from one letter;

‘Here is the extract from the officer’s letter— The orders in this district from Lord Kitchener are to burn and destroy all provisions, forage, etc., and seize cattle, horses, and stock of all sorts, wherever found, and to leave no food in the houses for the inhabitants. This applies to houses occupied by women and children only. And the word has been passed round privately that no prisoners are to be taken; that is, all the men found fighting are to be shot. This order was given to me personally by a general, one of the highest in rank in South Africa. So there is no mistake about it. The instructions given to the columns closing round De Wet north of the Orange River are that all men are to be shot, so that no tales may be told; also the troops are told to loot freely from every house, whether the men belonging to the house are fighting or not’.[xxv]

Dillon also quoted from a letter signed by William Clyne, of the Liverpool Regiment, which was published in the Liverpool Courier.[xxvi]

‘Lord Kitchener has issued orders that no man has to bring in any Boer prisoners; if he does he has to give him half his rations for the prisoner’s keep’.

‘WE TAKE NO PRISONERS NOW’

‘We take no prisoners now, One night this month some of our men lost their way and could not find the picket[.] They shouted out, “Where are you, lads?” The Boers answered, “Here we are,” and the poor chaps went up to them and were made prisoners. Next morning we were looking for them when the Boers opened fire on us. It did not last long. We turned the guns on them, and we soon made them shift. There happened to be a few wounded Boers left. We put them through the mill. Everyone was killed. About five Boers were brought in for not putting down their arms, and they all got shot the next day. I was on guard over them in the night, and you should have heard them praying when they knew they were to die next morning. They were takenout the next morning, made to dig their own graves, and two of the sections of my company went down about nine o’clock in the morning and shot them. The best thing to do with them is to serve them all alike.’

A further reference quoted by Dillon appeared in the Dublin Freeman’s Journal and National Press. The editor of the newspaper printed the letter and claimed it was from a senior ranking British officer whose identity could not be revealed for fear of reprisal. The letter was detailed and described tactics used by the Boers to fight the British.

The focus of the letter was the allegation against Kitchener and the officer’s self-justification for speaking out:[xxvii]

‘I have great hesitation in writing what follows, because it will seem incredible to most people. But I think it is necessary, because I am convinced that the man who conceived so diabolical an idea will take care to guard himself from the consequences, and impute the blame to others when the deed is done. Soldiers and regimental officers will be made to bear the blame, and, therefore, I consider the honour of the army is at stake, and I prefer that the obloquy should fall on the real author rather than on those among whom I have served for so many years, whose friendship I claim, and whose honour is as dear to me as my own. Lord Kitchener having, as he thought, caged his enemy, sent secret instructions to the troops to take no prisoners; that is, if the Boers, surroundedon all sides, find themselves unable to resist, and hoist the white flag as a token of surrender, they are to be shot down to the last man. Even now that the order has been given I do not believe that it will be fully carried out unless under the eye of Lord Kitchener or a few of his adherents. Some massacre will probably take place, because there are a few men who will do any deed to gain the favour of superiors. But I cannot bring myself to believe that the English and Irish soldiers will commit so dastardly a crime unless they have been previously worked upon and maddened by tales of supposed atrocities. Certainly many things have happened during the last fewmonths which I did not anticipate’.

Lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton

The issuing of illegal orders to execute prisoners was highlighted in the trials and sentencing of these Australian volunteers for shooting 12 Boers prisoners. Morant and Handcock were executed on 27 Feb 1902. Witton was sentenced to life imprisonment.

George Witton wrote a book on his return to Australia in 1904. He gave precise detail of the circumstances surrounding the trial and sentencing and the decision that they were compelled to obey orders from Kitchener that they believed were lawful and had to be obeyed.[xxviii]

Witton stated that Morant gave evidence that he had orders from their British superior, Captain Hunt to take no prisoners and these orders had been conveyed to them by Kitchener. Witton claimed that such orders were corroborated by Lieutenants Picton, Handcock and Morant and other commissioned and non commissioned officers who served with Morant.

Further evidence of orders was verified by Colonel. J. St Clair, Deputy Judge Advocate General and addressed to Major General Kelly, Adjutant General. The opinion dated 22 November 1901 written by St Clair after he had reviewed the report of the investigation conducted in November 1901.

His legal opinion about the existence of orders:

‘The idea that no prisoners were to be taken in the Spelonken appears to have been started by the late Captain Hunt and after his death continued by orders given personally by Captain Taylor.’[xxix]

The existences of superior orders that were illegal according to Military law and the Hague Convention were issued by Kitchener through his subordinates, including Captains Taylor and Hunt.

On 19 March 1902, shortly after the executions of Morant and Handcock, William Broderick, the Secretary of State for War admitted to the House of Commons:

‘That Boers captured in British uniforms were liable to be tried by Court Martial and shot. Lord Kitchener, he said, had already executed some of the enemy found committing this breach of the customs of civilized warfare’.

Denial of Due Process – Morant, Handcock and Witton

At the conclusion of the Courts Martial, the accused were not informed of the verdicts on the charges.

On 23 February, the prisoners were moved to the condemned cells at Pretoria prison with their fate still unknown. Kitchener finally confirmed their sentences on 25 February. He commuted Witton’s sentence to penal servitude and ignored the recommendations for mercy contrary to the Manual of Military Law for Handcock and Morant.

According to Woolmore, on 26 February 1902, each accused was escorted to the office of the governor of the Pretoria prison and informed of his sentence.[xxx] ‘After confirming the sentences Kitchener left Pretoria for Harrismith and the pretence was that he could not be contacted. The petitions of the prisoners and their legal representative, Major Thomas were a waste of time.’[xxxi]

A last desperate plea. Witton described Morant’s reaction to his sentence of death:

‘He requested to be provided with writing material and immediately petitioned to Lord Kitchener for a reprieve. Handcock at the same time also wrote, asking neither mercy nor anything else for himself, but begged that the Australian Government would be asked to do something for his three children. To Morant’s petition there came a brief reply from Colonel Kelly, second in command at Pretoria, stating that Lord Kitchener was away on trek. He could hold out no hope of reprieve, the sentence was irrevocable and he must bear it like a man. Handcock’s letter was returned to him without an acknowledgement. At the same time I sent two telegrams one to Mr Rail at Capetown, another to my brother in Australia. I was officially informed that they had been sent via Durban but I learned later that both had been suppressed.’[xxxii]

Witton’s story was not just confined to the efforts of the convicted. It also included their defence counsel:

‘During the day, Major Thomas visited us; the terrible news had almost driven him crazy. He rushed away to find Lord Kitchener, but was informed by Colonel Kelly that the Commander In Chief was away and not expected to return for several days . He then begged Colonel Kelly to have the execution stayed for a few days until he could appeal to the King, the reply was that the sentences had already been referred to England and approved by the authorities there. There was not the slightest hope, Morant and Handcock must die.’ [xxxiii]

Injustice to the end

Although the Manual of Military Law did not prescribe a process to appeal convictions and sentences, it did contain some checks and balances against excesses in the conviction and sentencing of accused persons.

Morant, Handcock and Witton were denied a final review by the Crown of their convictions and sentences. They were also prevented from communicating with their relatives, the Australian Government and most importantly, the sovereign King who could have examined their pleas for clemency. Had the executions been stayed by Kitchener for a few days, Morant, Handcock and Witton could have discussed their options with their legal counsel and sought advice from the Australian Government.

The days prior to the officers being advised of their convictions and sentences were characterised by a shameful orchestration by military command to deny the convicted any hope of review. This was contrary to the principles of justice embodied in the laws that governed the theory and practice of military law.

Kitchener ensured that Morant, Handcock and Witton were prevented from:

- contacting Australian government and / or their relatives;

- petitioning Kitchener for a stay in the execution of the sentences so they could consider their option of review;

- seeking, through their legal counsel, Major Thomas a review of the convictions and sentences by the King and judicial application for a common law writ to stay the executions pending review.

The fact that the accused, either acting on their own or through their counsel, Major Thomas were prevented from petitioning the King and exercising their legal right of appeal was a gross and illegal violation of their common law right to review their convictions and sentences.

Redress of Wrongs –Military Law

In addition to this right, the accused officers also had the right to redress a wrong in accordance with the Army Act 1898. Section 42 stated that an officer could redress a wrong of his commanding officer and may complain to the Commander In Chief ‘in order to obtain justice and who is hereby required to examine into such complaint and through a Secretary of State make his report to Her Majesty in order to receive directions of Her Majesty.’[xxxiv]

The Manual of Military Law explained the redress process for both officers and soldiers and stated:

‘The report to Her Majesty is to be made through the Secretary of State, the constitutional adviser to Her Majesty’.[xxxv]

Kitchener’s decision to carry out the death sentences within hours of the announcement is difficult to justify. The accused had been in close arrest since October 1901. A delay in proceeding with the executions for a few days would not have caused any prejudice to the British Crown and would have permitted the accused to consider their position with the advice of their counsel. The haste to proceed to execution blocked the accused from making contact with Australia and to keep the arrest and subsequent trials a secret from the Australian Government.

Denial of Appeal

A convicted person’s right is to be tried in strict accordance with the law and to retain the right of appeal and review. Morant, Handcock and Witton had been tried under the British system of justice, but were denied any recourse of appeal. The most aggravating aspect of the case was the Australian Government was not informed of their arrest and trial on serious charges and when sentenced, denied any contact with the Australian Government.

Opinions of senior counsel and community leaders

The evidence about the illegal treatment of these men by Kitchener has been examined. Some opinions include:

Scott Buchholz,MP: Tabled a motion in the House of Representatives on 12 February 2018. It contained an expression of sincere regret and apology to the descendants of these men for the manner in which Morant, Handcock and Witton were treated by Kitchener. It stated:[xxxvi]

‘Sincere regret that Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton were denied procedural fairness contrary to law and acknowledges that this had cruel and unjust consequences; and

Sympathy to the descendants of these men as they were not tried and sentenced in accordance with the law of 1902’.

‘Lieutenants Morant and Handcock were the first and last Australians executed for war crimes, on 27 February 1902. The process used to try these men was fundamentally flawed. They were not afforded the rights of an accused person facing serious criminal charges enshrined in military law in 1902. Today, I recognise the cruel and unjust consequences and express my deepest sympathy to the descendants’.

Published opinions from the following senior legal counsel and community leaders condemning the illegal and oppressive manner in which Morant, Handcock and Witton were treated. Part quotes include:

Geoffrey Roberston, AO, QC.[xxxvii]

‘They were treated monstrously. The case of Morant and Hancock, the two men who were executed, is a disgrace. Certainly by today’s standards they were not given any of the human rights that international treaties require men facing the death penalty to be given. But even by the standards of 1902 [0:01:30] they were treated improperly, unlawfully’. Lord Kitchener made himself unavailable on the day the sentences were announced. But they also had a right of appeal to partition the King through common law. Now both of those were denied to these me’.

Sir Laurence Street AO, QC, former Chief Justice NSWs. [xxxviii]

‘A gross injustice. I agree with the general tenor of everything that Geoffrey Robertson said. Their case represented a gross miscarriage of justice’.

Alex Hawke, MP. [xxxix]

Gerry Nash, QC.[xl]

Tim Fischer, AC, former Deputy PM[xli]

Greg Hunt former MP and Minister[xlii]

‘I actually agree with Geoffrey Robertson. Not only is he probably the most esteemed international jurist in the Human Rights space that Australia has produced in the last half century, but I think he’s right’.

Robert McClelland, former MP & Australian Attorney General[xliii]

David Denton, AM, KC[xliv]

Conclusion

Concentration camps were established in South Africa to house Boer families forcibly and illegally displaced by Britain’s scorched-earth policies. The camps were poorly conceived and managed and ill-equipped to deal with the large numbers of person illegally detained.

Kitchener’s treatment of Morant, Handcock and Witton was an appalling abuse of military power and illegal conduct. Kitchener should have been cited for perverting the course of justice a common law offence in 1902 ‘when a person prevents justice from being served on themselves or on another party’. [xlv] His conduct amounted to a failure to ensure Morant, Handcock and Witton were tried and sentenced in accordance with the law of 1902. The most grievous conduct was the denial of a right of appeal and issuing illegal orders to take no prisoners. His conduct in the Boer war and the Omdurman was contrary to provisions of the Hague Convention of 1899.

Recommendation

Given the evidence in this submission, Australian Councils and Government authorities should review whether Kitchener is a fit and proper person to be commemorated and whether memorials should be removed. While Councils celebrate the Memorials to Kitchener’s visit during 1910, it remains a stain on his conduct. It is difficult to reconcile the appalling loss of life in the concentration camps, the wanton destruction of property and summary executions with Memorials that celebrate Kitchener.

If Australian Councils and Government agencies accept on the balance of probability evidence of illegal conduct by Kitchener occurred then they have an ethical responsibility to address the injustice. Removal of Memorials and public spaces bearing his name should occur.

James Unkles

CMDR (Rtd)

[1] https://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/government/federal/display/95710-centenary-of-the-visit-of-lord-kitchener & https://heritage.brisbane.qld.gov.au/heritage-places/1911

i] https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/your-country-needs-you

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beowa_National_Park

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Omdurman

[iv] M. Gordon, Viewing Violence in the British Empire: Images of Atrocity from the Battle of Omdurman, 1898, Journal of Perpetrator Research 2.2 (2019), 65–100 doi: 10.21039/jpr.2.2.10 © 2019

[v] Ibid p. 68

[vi] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Horatio-Herbert-Kitchener-1st-Earl-Kitchener

[vii] https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/breaker-morant-executed

[viii] https://www.heraldscotland.com/opinion/13140565.kitchener-war-criminal/

[ix]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Kitchener,_1st_Earl_Kitchener#:~:text=Historian%20Caroline%20Elkins%20characterized%20Kitchener’s,into%20targets%20in%20the%20war.

[x] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emily_Hobhouse

[xi] https://www.britannica.com/place/South-Africa/Gold-mining#ref480657

[xii] https://theconversation.com/concentration-camps-in-the-south-african-war-here-are-the-real-facts-112006

[xiii] https://allthatsinteresting.com/boer-war

[xiv][xiv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-combatant

[xv] https://unidir.org/sites/default/files/publication/pdfs//the-role-and-importance-of-the-hague-conferences-a-historical-perspective-en-672.pdf

[xvi] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1902/mar/04/south-african-war-concentration-camps

[xvii] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1901/feb/26/conduct-of-the-war-in-south-africa

[xviii] HC Deb 26 February 1901 vol 89 cc1239-91

[xix] House of Commons Hansard 26 February 1901 vol 89 cc1239-91

[xx] House of Commons Hansard 26 February 1901 vol 89 cc1239-91

[xxi] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1901/feb/26/conduct-of-the-war-in-south-africa

[xxii] House of Commons Hansard 26 February 1901 vol 89 cc1239-91

[xxiii] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1901/feb/26/conduct-of-the-war-in-south-africa

[xxiv] Wolverhampton Express and Star newspaper of January 12 1901, p.2

[xxv] House of Commons Hansard 26 February 1901 vol 89 cc1239-91 1239

[xxvi] House of Commons Hansard 26 February 1901 vol 89 cc1239-911247

[xxvii] Freeman’s Journal and National Press, which is printed on page 5 of the issue dated January 15 1901

[xxviii] Witton, George, Scapegoats of the Empire, Angus & Robertson, Hong Kong, 1904

[xxix] Colonel. J. St Clair, A legal opinion dated 22 November 1901 & National Archives Office, England – PRO, WO, 93/41, p. 1189

[xxx] W.Woolmore, The Bushveldt Carbineers and the Pietersburg Light Horse, 2002, p. 128

[xxxi]W. Woolmore, op cit, p.128

[xxxii] G.Witton, Scapegoats of the Empire, 1907, p.142

[xxxiii] G.Witton, Scapegoats of the Empire, 1907, p.142

[xxxiv] Army Act section 42

[xxxv] MML pp. 362-363

[xxxvi] House of Representatives Hansard 12 Feb 2018, Scott Buchholz, MP, Mike Kelly, MP and Michael Danby, MP

[xxxvii] G.Robertson- extract of legal opinion 2013,& https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xxxviii] L. Street- legal opinion 2013, & https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xxxix] A.Hawke-address to House of Representatives- Handsard-15 March 2010 & legal opinion, https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xl] G.Nash, QC, The Trial, Conviction and Sentencing of Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton, Memorandum of Advice, pp, 32 – 35, 14 October 2013

[xli] T.Fisher AC, legal opinion & https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xlii] G.Hunt, legal opinion 27 June 2013, https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xliii] R.McClelland legal opinion & https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xliv] D.Denton, SC & legal opinion & https://breakermorant.com/?page_id=405

[xlv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perverting_the_course_of_justice