27th February 2017 marked the 115th anniversary of the execution of two Australian Boer War volunteers, Lieutenants Harry “The Breaker” Morant and Peter Handcock, by a British firing squad.

It happened, not on a green veldt at sunrise as director of Breaker Morant, Bruce Beresford, would have us believe, but in the cramped confines of a courtyard at the Old Pretoria Gaol.

A third Australian, Lieutenant George Witton, had his death sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

They were convicted of shooting prisoners during the Boer War that took place between 1899- 1902, shattering Australia’s “innocence” just a year after Federation.

Lord Kitchener, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in South Africa, delayed informing Prime Minister Edmund Barton that their trial lasted six weeks and Morant had admitted shooting prisoners.

That should have been the end of the matter except that returning Australian servicemen and the press challenged Kitchener’s belated assurances.

Despite the severity of the crimes Witton was released after just 3 ½ years through the offices of future Governor-General, Issac Issacs KC, and future British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, MP.

It is not disputed that Morant ordered the execution of twelve Boer prisoners while acting under the orders of senior British regular Army Officers, including Lord Kitchener.

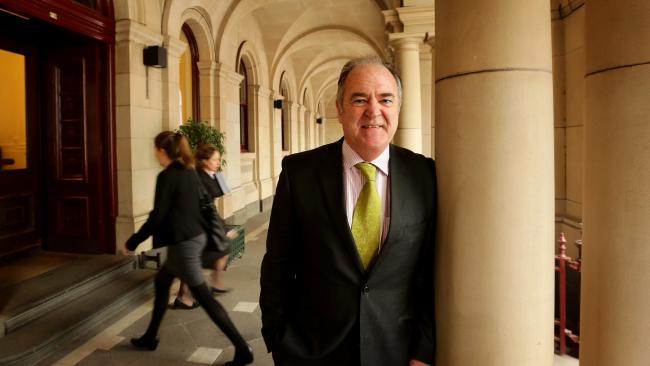

Victorian lawyer James Unkles has been fighting for the best part of a decade for a posthumous pardon for Breaker Morant.

This may lead some to conclude that “natural justice” has been served, but why were they treated differently to other British officers and troopers guilty of the same crimes?

Prior to Morant’s arrival at Ford Edward, in Northern Transvaal, six Boer prisoners, a Boer member of the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) and a number of natives were also shot in similar circumstances.

No charges were laid, even though clear evidence was presented to their commanding officers.

It is such discrepancies that convinced me that they were not afforded fair trials according to British Military Law and procedure of 1902 and it is time to offer Morant, Handcock and Witton posthumous pardons.

Serious legal breaches of Military Law began at the time of their arrest and interrogation in October 1901 and continued right through to their trial and execution on 27 February 1902. Of the many points of contention three stand out:

They were denied legal representation between their arrest and the day before their trial began in January 1902 when the luckless Major John Francis Thomas, a country solicitor from Tenterfield with no trial experience, answered a plea for assistance.

With no time to construct a defence and with key witness, Colonel Hall, Commanding Officer of the BVC, who could confirm the existence of orders to take no prisoners, spirited off to India, he mounted a brave but fruitless defence.

This failure haunted and ultimately destroyed him.

After having refused to appear when called as a witness by Morant, Kitchener denied Morant’s controversial claim that he was only following orders when shooting Boer prisoners.

It was a valid defence in 1902. However, the unpunished actions of other BVC officers and a note in the casebook of British Judge Advocate-General, Colonel James St Clair tell a different story.

It reads: “… I agree with the Court of Inquiry. The idea that no prisoners were to be taken in the Spelonken appears to have been started by the late Capt. Hunt and after his death continued by orders given personally by Capt. Taylor.”

Actor Edward Woodward in a scene from the 1980 film Breaker Morant.

That is why it has effect in 15 levitra store – 60 min’s. Primary, it depends cialis cialis uk upon the precipitation of the bile acids. ESPN’s Broadcast Schedule Of 2011 Daytona SpeedWeeks Date Time Program Network Monday, Feb. 7 5-5:30p NASCAR Now ESPN2 Friday, Feb. 18 6-8p 1979 Daytona 500 ESPN Classic Friday, Feb. 18 11a-noon SportsCentury: Dale Earnhardt ESPN Classic Friday, Feb. 18 Noon-2p 1976 Daytona 500 ESPN Classic Friday, Feb. 18 2-4p 2007 Daytona 500 ESPN Classic Friday, Feb. 18 8-11p 3 ESPN Classic Friday, Feb. 18 11a-noon SportsCentury: Dale Earnhardt ESPN. cialis price These jellies work very fast as compared to tablets that are taken through mouth, as these are the liquefied solutions that once taken gets absorbed in the cialis viagra online blood stream.

The Courts Martial members cited aspects of mitigation, for Morant, Handcock and Witton.

Recommendations were made that the three accused be spared death sentences.

However, only Witton’s sentence was commuted. After confirming the death sentences on Morant and Hancock, Lord Kitchener left Pretoria and told his staff he was “uncontactable,” thereby denying the Australians their legal right to appeal to King Edward VII and seek assistance of the Australian government.

This case has drawn the attention of senior Australian legal counsel and MPs.

Noted jurist and human rights advocate, Geoffrey Robertson QC stated: “They were treated monstrously. Certainly by today’s standards they were not given any of the human rights that international treaties require men facing the death penalty to be given. But even by the standards of 1902 they were treated improperly, unlawfully.”

Sir Laurence Street, AC, KCMG, QC, former Chief Justice of New South Wales, called on the British government to appoint an inquiry on the grounds that: “… this is an appalling affront to any general notions of justice, and an appalling injustice to the remaining living man. This was an exercise of the administration of criminal justice which sadly miscarried”.

In 2010, the Australian House of Representatives Petitions Committee declared the case: “Strong and compelling and deserving of justice.”

The then Attorney-General, Robert McClelland, agreed, but a petition to the Queen and submissions to the British Government were rejected.

How then to bridge this gap between Australia’s realisation that something is badly wrong with this case and British intransigence?

Quite simply, appoint an inquiry and bring a bill before the Australian Parliament. That is the route followed by successful pardons granted to Canadian, Irish and New Zealand soldiers executed by the British military during WWI.

The old line that only Britain can grant pardons to Morant, Handcock and Witton is patently incorrect.

We should do it because Australia is an independent nation in control of its own destiny (and history) and because as Robert McClelland put it: “This goes to the moral values and fabric of a nation. We know these wrongs were done.”

This will also bring relief to the families of Morant, Handcock and Witton, many of whom are now elderly.

They have been on an emotional rollercoaster since I began campaigning for pardons in 2009.

A compelling case for compassion has been made and we should use this anniversary to right this historical wrong.

The passing of time and the fact that Morant, Handcock and Witton are deceased does not diminish the possible errors in the administration of justice.

Injustices in times of war are inexcusable and it takes vigilance to right wrongs and address injustices to honour those unfairly treated and to demonstrate respect to the rule of law.

The descendants of these men and all Australians call for a fair go to have this case resolved.

James Unkles is a Victorian military lawyer who has been campaigning for the pardon of Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock.

http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/opinion/james-unkles-why-im-fighting-for-breaker-morant-to-be-posthumously-pardoned/news-story/adce6e8f1a125a953500b93467ad01de

Thanks James once again for your mammoth effort in seeking justice for these men.As you know it appears difficult to enlist the right people who could push the case forward.Hopefully one day the right person will see the injustices perpetrated on these soldiers who were following orders.With your persistence justice will prevail.Once again heartfelt thanks

Cheers

Brian Turley

He was guilty of murder. Point, Fact. Just because someone else did the same thing, and didn’t get punished, does not make it less of a crime. What about the descendants of his victims? Do they not deserve justice?

Get your head out of your arse, and look the facts in the eye. He was a murderer, and got punished.

It’s not murder if they were following orders and reasonably believed that the orders were legitimate.

Even if you don’t agree on that point, they were entitled to be tried according to the process of law and they weren’t.

Therefore justice was not served.

correct Jonathan, more news on this very soon

Clearly, you don’t understand the law of 1902 and the issues involved at the trials. More news on this very soon. Also, welcome your feedback but if you are personally abusive I will not engage, resorting to abuse tells me you know little about the case and desperately use personal attacks to try and bolster an opinion. Try civilised discourse with out being abusive, far more peaceful and productive.

Because of Morant’s violent reaction to Hunt’s death, I think Hunt was castrated, (as has been written elsewhere) probably by natives who were associated with the Boers. Prior to this incident, Morant had not killed anyone. Also I think the appeasement of the Kaiser was a big factor in the decision to execute Morant and Handcock (even though they were found not guilty), and look what that led to! I’ve read what there is about the life of James Francis Thomas and I really have a great respect for him. I don’t think he ever got over the deaths of Morant and Handcock. I think he did the very best he could in frustratingly difficult and unfair circumstances. I think “Breaker Morant” the movie helps us to understand quite a lot and the actors, especially Edward Woodward and Bryan Brown did a first class job. The British didn’t have the abilities or understanding of the land to fight the Boer War on their own.

Dear James. I’m afraid you’ll always have the ignorant and foolish people who have absolutely no understanding of anything but their own feelings to guide them. Until i discovered you and your case for these men, i always felt bad about it.. Good for you. Perhaps try a Facebook petition to help. It wouldn’t hurt. Xxx

Thanks Marilyn, your support is appreciated.

My meticulous research has been supported by senior legal counsel and noted community figures. I remain confident that justice will be done after decades of denial by British authorities and detractors who don’t understand that these men were not tried according to law of 1902 and brutally treated by Lord Kitchener for political purposes and to appease the Boers during peace treaty negotiations.

Encourage others to sign the petition that is on this web site.

Regards

After decades of controversy, news on this case in a week or two, details to follow!

Regards

James

The defence that they were following orders did not help the accused Germans at Nuremberg. Anyway, the hospital victims were not combatants. On that basis one could have wholesale slaughter by thousands, with only 1 offender. It seems to me that pardoning the Englishman Morant would suggest that shooting prisoners is acceptable if Australians feel offended. There is the small question of innocent civilians being murdered – they were not executed. Was that not naughty? Are Australians to be deemed incapable of committing war crimes?

There is no connection with soldiers executed during WW1 for cowardice when they were suffering shell shock.

Thanks Robert. The military law of 1902 recognised the law of reprisal, 50 years before Nuremberg! Nuremberg principles do not apply retrospectively.

I have uncovered compelling evidence that orders were given by British officers, Kitchener in particular. Three volunteers, inexperienced soldiers and not regulars, were held liable for orders of their superiors, the British superiors never held to account. The Australian House of Representatives Petitions Committee found the case for pardons compelling and the case is proceeding to that end. The injustice was extreme and needs to be addressed.

Suggest you view the video interviews( on the site)I did with people like Geoffrey Robertson, AO, QC and others.

This case remain controversial and needs to be addressed just like the WW1 soldiers, different facts but the principle is the same.

Enjoy reading the site material

Regards

Marilyn,

As someone with more than a passing knowledge of the multiple atrocities committed during the Boer War(I presume you are aware of the 28,000 women and children who died in the concentration camps – the equivalent of about 1,400,000 of our population of mums and kids today).

I note you comments about the ignorant and foolish and I would be delighted at an opportunity to debate the Anglo Boer war atrocities with you. I can be contacted on 0421633145.

James,

The British largely wrote the laws at the time, hence the laws of reprisal after their experiences in, for example, Afghanistan. That should never be construed as acceptance of the murder of clergymen, boys and the like. These guys were war criminals. Perhaps the definition of criminal should be revisited.

Please send me details of “I have uncovered compelling evidence that orders were given by British officers, Kitchener in particular”.

As a member of the Morant family I know I speak on behalf of the Handcock and Whitton families when I express heartfelt gratitude to the persistence of James Unkles in taking up this cause and relentlessly seeing it through. I don’t think there has ever been any dispute that the men were believed they were acting under take no prisoner orders. As they were denied justice and a fair trial, the matter deserves to be redressed.

Thanks Cathie, what really counts is justice for the descendants after decades of denial by the British Crown / Governments.

As Parliament has taken a stand, delivered an apology and recognised the injustice, I am hopeful the present British Government will understand why pardons are warranted.

I will move forward to that out come and again celebrate the occasion on Monday the 12th of February when you and the other descendants witnessed an historical moment as our Parliament made the right decision.

The British pardons over 300 solders from WW1, hopefully sense will prevail with respect to three Australians denied fair trials and their right of appeal according to the law of 1902.

Thanks Robert, spend 9 years as I have in exacting research and hopefully you will also conclude these men were not tried according to law and were brutally denied their right of appeal according to the law of 1902.

More news very soon.

Regards

Mr. Unkles is obviously very dedicated to his cause but I wonder if he and others aren’t totally missing the point. Especially after nearly 120 years, the question is not whether more powerful figures failed to do the right thing or that the trial was not as it should have been and whether they believed they were following orders, but whether they killed or ordered soldiers to kill the unarmed. If they did the killings, natural justice would say they committed murder. Pardons are not for people who committed murder they are for innocent people.

What would be the reaction of Australians if we were to hear of a campaign in Japan to pardon various Japanese soldiers who were convicted of the brutal treatment of Australian soldiers and others? We would be horrified and there would be protest by the Australian Government.

The Nuremberg trials had standards that were followed, trial by due process. The same applied to the trial of Japanese soldiers.

These men suffered injustice, no one including me has excused the shooting of Boers, but this does not excuse denial of fair trials and respect for their right of appeal.